Juveniles Vs. Adult Courts

An (Im)Partial Story

By: Casey Chafin and Matthew Voggel

Pennsylvania – and the United States as a whole – may be traveling away from a recent history of harsh attitudes and treatment of youthful offenders.

Tough-on-crime policies generally got tougher during 1990s. U.S. criminal penalties, including those for juveniles, became among the harshest in the world.

Although most countries draw the dividing line between juvenile and adult at age 18, some define a separate, more lenient legal category for young adults up to ages 24 or 26, according to the group “Protection of Minors,” a European coalition working to reduce juvenile delinquency figures. Moving juveniles below the age of 18 to adult court is rare in most of the world but has become widespread in this country.

For years, United States stood alone as the only country to allow mandatory sentences of life without parole for juveniles. Now the nation’s highest court has declared those sentences to be unconstitutional, and Pennsylvania has now begun a prolonged process of resentencing the almost 500 juveniles lifers in its prisons. Over 300 of these cases are to be reheard in the Greater Philadelphia area, while just 37 will be retried in Allegheny County, according to Public Source.

First- and second-degree murders make up the bulk of the cases. Research has shown that the majority of these former juveniles were originally sentenced in the 1990s.

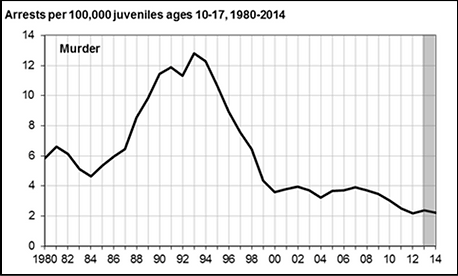

That decade of harsh sentencing coincided with an increase in overall arrests of juveniles, according to the Census of Juveniles in Residential Placement. The chart below illustrates a spike of arrests per 100,000 juveniles between 1987 and 1993:

Wes Oliver, director of the criminal justice program and professor of law at Duquesne University, described the 1990s as a time where judges were giving longer sentences, while the state actually saw the number of trials decrease. This trend was spurred by more defendants agreeing to plea bargains.

The trend also changed what was considered the “normal” sentence for a given crime. Oliver said that throughout history, sentences have been determined by what the current “normal” sentence is for that given crime. In other words, sentence lengths are influenced by public opinion over time. “No one puts a robber on a scale and goes: ‘Oh yeah, this looks like seven years,’” Oliver said.

Both Oliver and his colleague Bruce Ledewitz, law professor at Duquesne University, pointed to the increasing power of county district attorneys as an important factor affecting harsher penalities. Ledewitz who served as Secretary of the National Coalition to Abolish the Death Penalty from 1985 to 1990, cited a spike in death penalty cases during the 1990s. (See “Changing Views on the Death Penalty in the United States” by Richard C. Dieter.)

He named two factors that affected the number of death penalty cases in Pittsburgh and Philadelphia. Similar factors influenced the treatment of juveniles in the state’s two largest cities.

First, new rules set down at the federal level—as well as changes in state statutes—gave district attorneys greater discretion and power in criminal court process. During the 1990s, the law-and-order DAs in Philadelphia asked for the death penalty in almost every murder case, Ledewitz said, and they continue to do so. “Generally speaking, that does not happen in Allegheny County,” he said.

In contrast to Eastern Pennsylvania, Western Pennsylvania has a higher number of union members, a larger Catholic population and less racial tension. These factors, as Ledewitz described, have consistently led to the election of a more compassionate DA in Pittsburgh than in Philadelphia. As a result, the number of death penalty cases, as well as juveniles subjected to mandatory life-without-parole sentences, in Allegheny County is a fraction of those from Philadelphia.

Kathleen Michon, a professor of law at Northwestern University, has written that there are three ways to decide if a juvenile will be moved to adult court: the prosecutor can request it, the judge can decide to move the case or, in some states like Pennsylvania, certain crimes will automatically be moved to adult court.

Until recently, if a juvenile was tried as in an adult court, a conviction carried a mandatory life sentence. “Fair?” Ledewitz asked rhetorically. “I don’t even know the word.”

But now the U.S. Supreme Court has declared the mandatory part unconstitutional.

Wes Oliver described the constitutional prohibition on “cruel and usual punishment,” which formed the legal foundation for both the Miller and Montgomery cases, as only a matter of where “the norm” lies. And the current wave of resentencing in Pennsylvania may be relocating that norm for the court’s treatment of juveniles.